Montessori and Traditional Education, How Are They Different?

One of the questions we get asked all the time is about the differences between Montessori schools and traditional education. I discuss this question in the introduction to my new, soon-to-be-published book, Why Montessori Works – Ten Secrets.

I’m happy to share this excerpt from the new book, and would love your feedback!

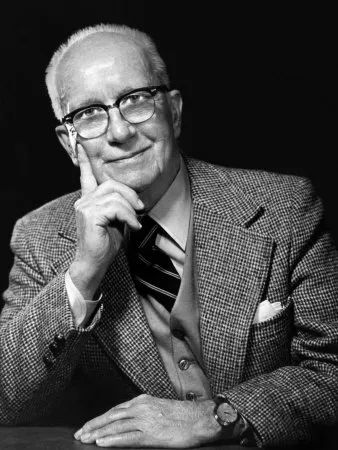

Our children are the most brilliant learners as well as the most creative and loving people on the planet. The well-known American philosopher, systems theorist, architect of the geodesic dome, and inventor Buckminster Fuller may have said it best: “Everyone is born a genius, but the process of living de-geniuses them.”

Our schools and some aspects of our culture de-genius children. Up to 60% of some populations in the United States fail to learn to read. Every year, over 1.2 million students drop out of high school every year. That's a student every 26 seconds – or 7,000 a day. What a tragic waste of talent!

Maria Montessori, Italy’s first woman physician and three-time nominee of the Nobel Peace Prize for her remarkable insight into the life and the potential of children, wrote more than sixty years ago:

When the independent life of the child is not recognized with its own characteristics and its own end, when the adult man interprets these characteristics and ends, which are different from his, as being errors in the child which he must make speed to correct, there arises between the strong and the weak a struggle which is fatal for mankind.

For it is upon the perfect and tranquil spiritual life of the child that depends the health or sickness of the soul, the strength or weakness of the character, the clearness or obscurity of the intellect. And if during the delicate and precious period of childhood a sacrilegious form of servitude has been inflicted upon the children, it will no longer be possible for men to accomplish great deeds. (Montessori, 1943, p. 20)

Every child is unique

Montessori clearly warns us that unless we understand the true nature of children, and give them the help they need, when they need it, they may lose their brilliance. And we see it around us every day. I have surely seen it; I think we all see it if we are willing to really look. Although much of my work has been in private Montessori schools, I have also had the opportunity to work in large urban public schools serving low-income families in Chicago, Phoenix and Savannah, both as a teacher and as a teacher educator. Some of the children I have taught and observed have faced tremendous obstacles. Some have an inner resiliency to get beyond the obstacles, while the eyes and minds of other children have seemed to grow dull. In many cases, they are bored.

I have seen four-year-olds told by their teacher that they were too dumb to learn. I have seen a five-year-old beaten with a broom handle and the administrator denying vehemently what I had seen with my own eyes. I have seen a six-year-old drawing his self-portrait in a pool of blood because he expected to be shot to death as his father had been. In a hospital I visited in East LA, I saw children who were abused – one young child with nineteen bones broken by his father, another one with scars all over his lower body where his mother had dipped him into boiling water after he wet his pants once too often.

But I have also seen the ones I like to call “the shining ones,” those little ones who are alive to possibilities within themselves and within their environment.

These children are the ones that are eager to learn and seem to love life itself. It saddens me and makes me angry that every child does not have opportunity to learn in a safe, supportive environment. We have a society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, yet cruelty to children goes on in many families and schools and we do little about it. In many cases, young parents and educators simply do not have the adequate information and maturity to handle the needs of growing children.

I know teachers who worked night and day (and weekends) to serve the children they work with every day. And I have worked with others who believed it was useless to even try and teach the children because of their socio-economic background, arguing that if they do not know how to sit at a table for a meal, how can they learn their letters? I would sit and argue with them that in my own experience, it is possible to teach any child, no matter what. But first you have to love them and meet them precisely where they are, not where some standardized curriculum says they are supposed to be. Only then can you help the child move forward. And I saw the eyes open in some of the teachers who realized that, yes, perhaps their children could learn after all.

I wrote this book for every parent and caregiver who desires the best for the children they love. I wrote this for every parent and educator who wants to understand what Montessori really is, what these secrets will reveal about how we can all learn to be more effective, and why such tremendous interest is growing throughout the world. And I wrote this for Montessori educators, striving to refresh and deepen their own understanding of what we do every day.

More than a method

Montessori education is more than just a method of education. It is a message of who we are, and how we can treat one another in a more respectful way. Montessori’s original thinking has affected the world far more broadly than in the tens of thousands of schools bearing her name. Child-size furniture and tools such as brooms and rakes are now available everywhere. The idea of hands-on learning is in schools everywhere. The idea that young children can and want to learn, without being pushed or punished, is more readily accepted.

But what is Montessori education, really? Often misunderstood or partially understood, Montessori is sometimes characterized on one hand as a place where children get to do whatever they want and on the other hand, a place that is too structured for creativity to be able to flourish, with a series of lessons that need to be presented mechanically correctly. Neither is correct. As usual, we have to seek the truth in the middle way.

In the chapters of this book, we will look at the secret ingredients that make Montessori schools so reliably successful all over the globe. In truth, not every Montessori school is successful, since whatever any school or teacher does passes through his or her consciousness and training. But when it is done well, there is nothing better. Even when it is not done so well, it is better than many alternatives.

The work of Montessori graduates is stunning. Here are just a few former Montessori students who have done their part in changing our world and who gratefully acknowledge Montessori as a key factor in what taught them to think clearly and creatively.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin, founders of Google, changing the way the world computes.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, changing the way the world buys books and pretty much everything else as well.

Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia, changing the way we access and share information.

Julia Child, TV chef and author, changing the way we cook and watch cooking shows.

Berry Brazelton, Pediatrician, child psychiatrist and author, changing the way we parent, whose child-oriented philosophy of parenting has influenced countless families to raise children who are “confident, caring, and hungry to learn.”

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Colombian-born Nobel Prize winner in literature, changing the face of literature.

Will Wright, founder of the SIMS games, changing children’s ideas of how they can create their own prepared virtual environment.

Joshua Bell, Grammy Award winning violinist, demonstrating creativity and beauty.

Yo Yo Ma, internationally-acclaimed cellist, United Nations Peace Ambassador, winner of 15 Grammy Awards, Presidential Medal of Freedom & National Medal of the Arts, demonstrating passion for all forms of music and beauty.

Helen Hunt, Oscar-winning actress and spokesperson for Montessori education.

Anne Frank, memoirist & author, forever opening to us the courage and maturity of a teenager.

Erik Erickson, psychologist & author, who found Montessori’s ideas so compelling that he earned a Montessori teaching certificate although he never taught.

HM Queen Noor of Jordan, U.N. Advisor, humanitarian activist, memoirist and wife of the late King Hussein of Jordan.

Peter Drucker, author, management consultant, awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work on human relationships in the workplace.

Princes William and Harry, changing the way the world sees royalty. William someday will be the King of England.

William and Kate’s firstborn son George, attended a Montessori school at age 2 ½, and we shall see what he may contribute to the world.

And these are just the famous ones… I could add your children and my children, and if I had room and knew all the names, I probably should! Many thousands of children have gone through Montessori and shine in their respective areas. Not every child shines in every way. But if each child gains something more than he had when he walked in the door, then yes! If the child has learned to love learning, then yes! We are doing our jobs.

So, let’s take a look at some of the general characteristics of both traditional and Montessori schools, to better highlight what Montessori education has to offer, noting that some features might be called “defining features.”

Traditional Schools

- Traditional public schools tend to have a highly centralized governance of curriculum and schedules.

- Funding is tied to test scores.

- Teacher education courses are largely theoretical.

- Traditional education relies on direct teaching of the entire class – the teacher is the agency of the children’s learning because she teaches.

- There is an established curriculum of reading, writing and arithmetic, carefully parsed out per month, per week and per day, generally driven by a textbook that aligns to the tests that will be taken.

- Students at a specific grade level have the same program, and a child either gets it or fails.

- All the children are the same age in a classroom.

- Teacher is accountable to teach.

- Environment includes the teacher’s desk and a whiteboard, children’s desks and chairs with materials largely for the teacher to demonstrate with.

- Interest of children often has little bearing on covering the curriculum.

- Teachers are the arbiters of most conflicts. According to one study, teachers solved 80% of conflicts between children in traditional classrooms.

- Maintaining discipline is a function of the teacher.

- Work periods are specifically delineated for each subject and children must stop what they are doing if it is time for the next subject.

Montessori schools

- The majority of Montessori schools are independent, while a growing number are charter schools or are within public schools. Each charter sets its own goals and standards, and may or may not choose to follow Common Core. In most all cases at the elementary level, children sit for standardized tests.

- Funding may come from several sources, often primarily tuition.

- Teacher education courses are based in large part on practical sequences of lessons in major curriculum areas as well as classroom management.

- Individuals and small groups are taught based on observable needs by introducing them to materials that serve to teach – the child is the agency of his own auto-education.

- The primary goal is to nurture individuality.

- It is possible to accelerate children at their own rate, since there is a three-year age span and multiple materials that can take a child from the simplest to the more complex understanding, and no child is asked to perform at a level lower or higher than he can manage.

- Mixed ages, three-year age span offers opportunity for leadership and natural profiles of abilities to stand out.

- Children are accountable to learn and are taught simple time management skills.

- Prepared environment includes plenty of workspace on tables and floor rugs with a rich assortment of hands-on material children are shown how to use and are allowed to choose when they are ready to learn the skill contained in the material.

- Discipline in a normalized class is largely self-discipline.

- The individual interests of children are seen as expressions of individuality and are respected in daily choices.

- Children learn conflict resolution skills and apply them in about 80% of conflicts in Montessori classrooms.

- A two- to three-hour uninterrupted work period is provided each morning, with children free to work on the material of their choice, within the parameters of what the child has been shown and is ready to understand.

It works!

As I have meditated deeply over many years on the question of what education is, what it should be and what it could be, I keep coming back to my roots in Montessori. It is without question successful all over the world. The amazing thing is that no matter what the age of children, Montessori as a system, works. I have seen it work all over the United States, in orphanages in South Africa and Colombia, schools throughout Russia, Latvia, Czech Republic, Sweden, Italy, rural Mexico, urban Mexico, South Korea, Australia and China. It works everywhere there are children.

It began with Maria Montessori and her first school in 1907 with preschoolers, then advanced into elementary, then went into infants and toddlers. In recent decades it has expanded into adolescent and high school programs. There are even Montessori programs for Alzheimer’s patients and end of life care. It is rather astonishing that one system can accommodate the needs of any stage in life. What are her secrets? How can one system meet the needs of anyone at virtually any age?

Let’s find out!